Exploring the ecological role of an apex scavenger, the Andean condor

- IBCP

- May 13, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Jun 17, 2025

13 May, 2025

By Paula Leticia Perrig

Andean Condor at a carrion station monitored by Paula Leticia Perrig and colleagues. Photo courtesy of Paula Leticia Perrig.

Vertebrate scavengers play a vital role in supporting ecosystems and human well-being through their contributions to nutrient cycling, food web dynamics, and the control of infectious and parasitic diseases. Obligate scavengers, including many vultures, are particularly efficient at consuming carrion and can control for diseases and pests that develop when carrion persist for long periods of time. Unfortunately, however, vultures are now among the most threatened birds in the world. In South America, the Andean Condor (Vultur gryphus) is an apex, obligate scavenger that is declining across its range and designated as vulnerable to extinction. In response, I have been working with my colleagues at CONICET and the Universidad Nacional del Comahue in Argentina to (1) assess and raise awareness about the ecosystem services provided by Andean Condors and other native scavengers, and (2) evaluate how the presence of Andean condors influences scavenger assemblage structure and carrion removal rates.

Scavengers at a carrion station in Rio Negro, Argentina. Photo courtesy of Paula Leticia Perrig.

Thanks to in part to funding from IBCP, we addressed these goals in several ways. Analyses of camera trap data at 15 natural carcasses and 32 experimental carrion stations with camera traps in Rio Negro, Argentina, indicate that obligate scavengers play a central role in carrion removal rates. These data further reveal that there are significant economic benefits of conserving condors and other scavengers among ranchers, many of which perceive scavengers as harmful to livestock. Between December 2021 and 2023, we monitored fresh carcasses of sheep in open grasslands. To find these carcasses, we conducted periodic surveys of the main roads near our study area and contacted ranchers to get updated information of livestock mortality.

Camera traps placed near carrion show visits by mammals and raptors in Rio Negro, Argentina. Photos courtesy of Paula Leticia Perrig.

We staked each fresh carcass found to prevent it being dragged away and monitored its consumption through a camera trap installed at a distance of ~5 m; camera traps were removed after carcasses had been completely consumed. In addition to monitoring livestock carcasses, we deployed experimental carrion stations consisting of 3-4 cow heads obtained from a local slaughterhouse (in San Carlos de Bariloche city, Rio Negro). These experimental stations were placed in ranches in our study area, in randomly selected open sites located more than 1 km apart from each other. For both natural and experimental carrion stations, we recorded the initial and final biomass available by weighing the carcass in the field (using portable scales).

Andean condor distribution in Patagonia based on GPS locations (in grey) of 40 Andean condors tracked with satellite devices. The insert shows our study area (Rio Negro province, Argentina) and the location of sheep carcasses (blue dots) and experimental carrion stations (red dots) monitored with camera traps inside and outside the Andean Condor’s range. Map courtesy of Paula Leticia Perrig.

We collected 71376 camera trap photos of animals at 15 sheep carcasses and 32 experimental carrion stations and used the photos obtained from our camera traps to identify scavenger species as well as numbers of individuals feeding at carcasses we monitored. We detected 16 different species exploiting carrion, including 5 raptor species and 8 mammal species, and 3 obligate and 7 facultative scavengers. Up to 8 species were recorded at a single station, including 5 raptors and 8 mammals.

We monitored 15 natural carcasses and 32 experimental carrion stations with camera traps in Rio Negro, Argentina between December 2021 and 2023. Photos courtesy of Paula Leticia Perrig.

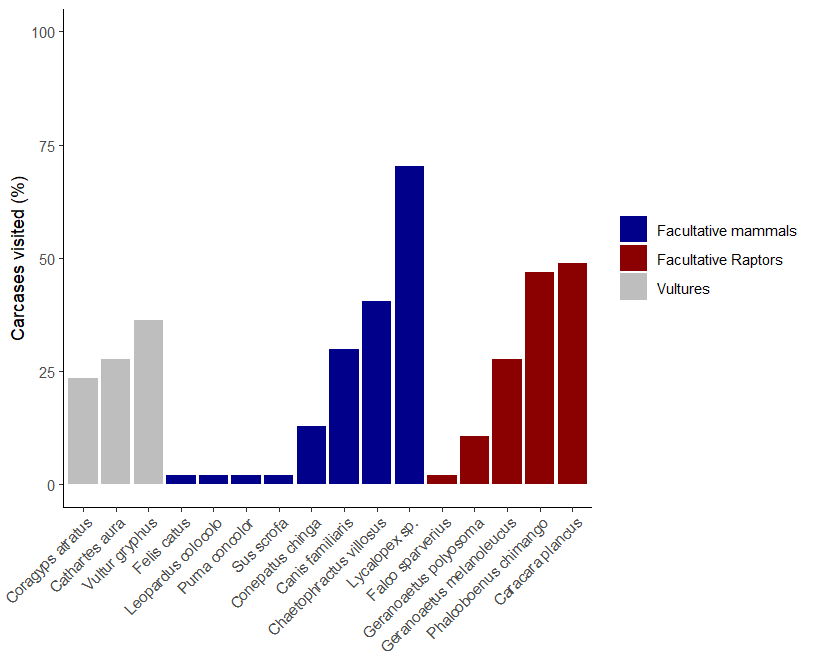

Dominant scavengers were foxes (Lycalopex sp., present at 70% of stations) and Crested Caracara (Caracara plancus; present at 49% of stations). Andean Condors were present at just over a third (35%; 17 of 48) carrion stations monitored, with a mean abundance of 11 individuals (range: 1-32). We also found a positive correlation between the rate of carrion consumption and the abundance of both obligate and facultative scavengers (respectively, β = 0.03[95% CI: 0.04 - 0.03]; β = 0.06[0.18-0.12]). Future analyses will allow us to explore the influence of condor presence and environmental factors on scavenging dynamics.

Species recorded visiting carrion stations via camera traps in cattle ranches in northeastern Rio Negro, Argentina. Vultures are indicated in gray, facultative scavenging raptors in red, and facultative scavenging mammals in blue. Figure courtesy of Paula Leticia Perrig.

Many scavenger species are perceived by ranchers as harmful to livestock, a belief used to justify their persecution. In the absence of scavengers, however, livestock producers would be legally required to remove carcasses from their fields. Thus, to demonstrate the importance of scavengers’ clearing livestock carcasses, we made an economic estimation of this ecosystem service. We focused on the western region of our study area, covering approximately 70 km². Based on the consumption of sheep carcasses monitored in this area, we estimated an average scavenging rate of 1.4 kg/hour and that scavengers in the area could consume 313 sheep per year. If a worker takes half a day to locate and bury a carcass, it would cost approximately ARG$3,222,475 (US$2,862) annually to dispose of an equivalent number of carcasses as those consumed by scavengers, highlighting the economic benefits of scavenger conservation.

Photos from student workshops promoting condor ecology and awareness. Photos courtesy of Paula Leticia Perrig.

Spreading the word about such benefits may help mitigate persecution and the use of poisons, which are among the main conservation challenges currently faced by the Andean Condor. To this end, we visited 12 elementary schools to teach about condor ecology and the ecosystem services condors provide. We delivered workshops to teach about local wildlife, and scavengers in particular, and the contributions these species make to human well-being. We also compared students’ perceptions of condors and other native species to evaluate whether these changed after our activities.

One of 71,376 camera trap photos of scavengers at carrion stations in Rio Negro, Argentina. Photo courtesy of Paula Leticia Perrig.

Preliminary analyses of the data indicates that our workshops have broadened students' understanding of ecosystem services provided by condors and other native wildlife in Argentina. In addition to the workshops mentioned above, we have disseminated our results to the public through approaches including participating in a local radio show and conferences including the XXX Argentine Ecology Meeting in 2023, in Bariloche, Rio Negro, and the XX Argentine Ornithology Meeting in 2024, in Miramar de Ansenuza, Córdoba. We are currently preparing three manuscripts with the results of this work. After these articles are published, they will be disseminated in social media and through participating in local radio show popular among ranchers in our study region.

Condors were present at approximately 35% of carrion stations in Rio Negro, Argentina. Photo courtesy of Paula Leticia Perrig.

Comments